Armillaria Root Disease

Armillaria ostoyae

Key Wildlife Value:

Armillaria ostoyae creates short-term snags of any size and all sizes of down wood, by killing and decaying the root system and butts of host trees. Canopy gaps resulting from armillaria root disease expand slowly, resulting in a more diverse stand structure and at times a more diverse plant species composition, as resistant or non-host trees, shrubs, and forbs are released or become established from the infection center outward, following the slowly expanding fringe of dying host trees. Bark beetles frequently are attracted to trees infected with A. ostoyae, providing good foraging habitat for woodpeckers.

Distribution in Oregon and Washington:

Found throughout Oregon and Washington. (See also Important Habitats and Spread Dynamics).

Hosts:

All conifers and hardwoods Oregon and Washington may be infected and damaged by A. ostoyae (a different Armillaria species, A. mellea, is associated with hardwoods in California). However, host susceptibility to mortality and pathogen virulence can vary widely from site to site, even among nearby locations (Table.fid-2). For this reason, identification of the susceptible host species at any particular site must be based upon field observations. Generally-speaking, grand fir and white fir growing east of the Cascades crest and in southwestern Oregon are most susceptible, being frequently infected and killed. Douglas-fir in northeastern Washington also is often infected and killed, as is ponderosa pine in southcentral Washington. Outside of southcentral Washington, however, ponderosa pine usually is quite resistant. Western larch, incense-cedar, Alaska yellow-cedar and Port-Orford-cedar are generally resistant. Most hardwoods appear to be tolerant. However, older California black oak and Oregon white oak are often damaged, and tree uprootings of these oaks in urban areas are frequently associated with armillaria root disease

Diagnosis:

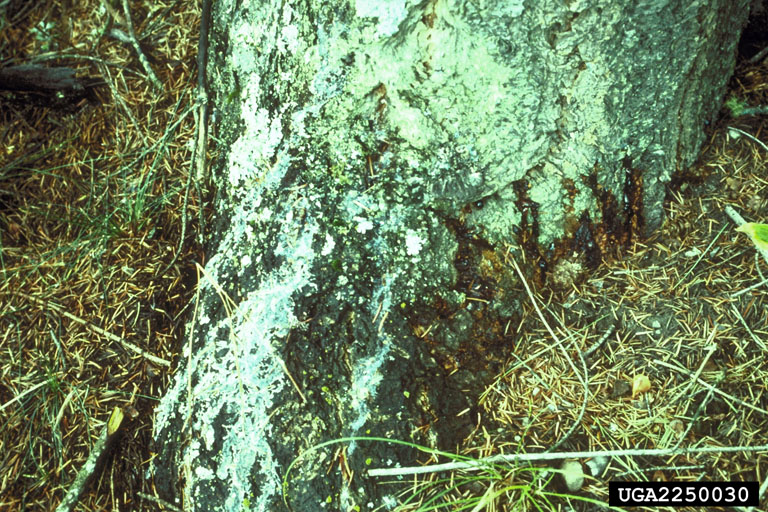

Infected conifers often display heavy resin flow and soaking at their bases that may extend from beneath the soil line to several feet up the bole.

Common crown symptoms include crown dieback, reduced shoot and foliage growth, and thinning, yellowing foliage.

In young conifer stands regenerated following harvest activities, look for a pattern of dead or missing trees associated with large stumps.

Other, non-pathogenic species of Armillaria that commonly occur as saprophytes on dying and dead trees and stumps are often confused with A. ostoyae. They may be distinguished from A. ostoyae based on the insubstantial nature of their mycelial fans (can be easily rubbed off with the fingers), lack of evidence of tree reaction, such as resin flow, bark soaking, or fan imprints on the sapwood or bark, and lack of other classic root disease symptoms in the surrounding stand.

Bark beetles, particularly fir engraver in grand fir and white fir, frequently colonize infected trees. Armillaria root disease may sometimes mask the presence of other diseases, especially heterobasidion root disease, so careful examination is required for accurate diagnosis of disease conditions on a site.

Life History:

Armillaria root disease infects new hosts when uninfected roots of susceptible trees contact infected stumps or roots. The fungus grows across root contacts and invades the root tissues of new hosts. It is able to spread along both live and dead roots. Spread also occurs to a lesser extent by rhizomorphs, which can grow a few feet through soil to infect nearby host roots. Fungal growth through the root results in reduced uptake of nutrients and water and usually kills the tree while it is standing. Once infected trees die, the fungus continues to live on-site as a saprophyte in large stumps and large roots for at least 35 years. Infection by wind-dispersed spores is believed to be rare.

A. ostoyae can differ markedly in its host preferences and virulence from site to site. The reasons for this are largely unknown. On infested sites that contain a mixture of tree species, armillaria root disease usually affects some of the species while others appear tolerant or resistant. Sometimes, however, every tree species on-site is affected.

Most fires have little effect on the survival of A. ostoyae on a site. Only those fires intense enough to destroy entire root systems are detrimental. Fire, however, sometimes may favor site occupancy by less-susceptible species, reducing the expression and expansion of disease.

Important Habitats and Spread Dynamics:

A. ostoyae is the most geographically widespread root pathogen throughout southwestern Oregon and areas east of the Cascades crest, where it may be active in stands of all developmental stages and sometimes forms very large infection centers up to hundreds of acres in size. West of the Cascades crest (excluding southwestern Oregon), expressions of disease associated with A. ostoyae are much less prevalent and activity is associated most frequently with young stands less than 30 years old and individual stressed trees. A. ostoyae is probably present in most Pacific Northwest conifer stands as a saprophyte, but when favorable conditions arise, it can become actively pathogenic.

Armillaria root disease is often associated with trees under stress. It commonly is found where trees encounter difficult growing conditions, such as mechanically disturbed, compacted, or droughty sites, where trees have been planted poorly, or where they are not well adapted to the site. Tree killing by A. ostoyae often increases 1 to 2 years following prolonged insect defoliation or severe drought. Most of the significant armillaria root disease activity in Oregon and Washington tends to occur under the following susceptible stand and site conditions:

- Douglas-fir or noble fir plantations less than 30 years old west of the Cascades crest in northwestern Oregon and in the Coast Range of Oregon and Washington.

- Mixed conifer stands east of the Cascades and in southwestern Oregon with previous harvest entries, especially those with multiple previous entries.

- Stands regenerated with seed sources or species not well adapted to the site.

- Sites with significant levels of soil displacement or soil compaction.

- Plantations established with poor planting techniques.

Continuous cover of highly susceptible species provides favorable habitat, especially when large infected stumps are also present, such as in partial cut stands. Armillaria root disease usually intensifies when infection centers and adjacent areas are regenerated with highly susceptible species. This is because armillaria root disease spreads primarily through root-to-root contact between infected and uninfected host trees and stumps. Long-distance spread is thought to be uncommon. Colonized stumps and infected trees serve as “centers” of gradually expanding root disease infection areas as the fungus slowly moves down colonized tree roots and up the roots of previously uninfected individuals. Infection centers expand at a rate of about 30 cm (1 ft) per year. The distribution of infection centers may be diffuse, with diseased individuals or small groups of 2 to 3 trees occurring scattered throughout the area of infection, or discrete, with discernable margins marking the transition from aggregations of diseased trees to healthy forest. Some centers exhibit fluctuating amounts of mortality over time, and some may appear to become inactive. Small infected stumps less than 15 cm (6 in) in diameter do not contribute to maintaining armillaria root disease on a site.

Opportunities for Manipulation to Increase Wildlife Habitat:

East of the Cascade Mountains and in some portions of southwest Oregon, when the remainder of the stand is regenerated using fairly resistant species, it may be desirable to retain some untreated areas containing selected armillaria root disease centers to provide a continuing supply of short-term snags and down wood.

Unlike laminated root rot or heterobasidion root disease, armillaria root disease is not well suited for employing the strategy of buffering to minimize spread to adjacent managed areas containing susceptible hosts because 1) A. ostoyae has a wide host range and also is able to progress along dead roots, so it is very difficult to create an effective buffer in most situations, 2) it is believed to be already present to some degree in most stands, and 3) its potential activity is difficult to assess in unaffected areas because the fungus appears to behave somewhat opportunistically, sometimes not becoming apparent until trees experience stress.

In western Oregon and Washington, little opportunity exists for manipulating A. ostoyae to increase wildlife habitat because armillaria root disease typically plays a minor role in Westside forest cover dynamics. In instances where it causes significant impacts it usually occurs secondary to primary stressors such as drought, poor planting techniques, offsite planting stock, site disturbance, etc.

Potential Adverse Effects:

Armillaria root disease can cause undesired growth loss and tree mortality. On the Eastside and in southwestern Oregon, armillaria root disease may create large openings where highly susceptible species die before attaining large size. Ground fire severity may increase as a result of the abundant down wood in infection areas. Trees killed by armillaria root disease may pose safety hazards because they are predisposed to tree failure.

How to Minimize the Risk of Adverse Effects:

The adverse effects of armillaria root disease are best mitigated by practices designed to minimize current and future tree stress or to encourage the growth of less susceptible species. During stand entries, minimize site disturbance and soil compaction as much as possible by controlling the size and type of equipment, restricting operations when soil is saturated with moisture, limiting skid trails and yarding corridors, and minimizing activities that cause soil displacement and compaction, e.g. tractor piling. Regenerate stands using planting stock and species that are well adapted to the site. Encourage vigorous root development by relying on natural regeneration or by promoting proper planting techniques.

When regenerating or treating sites where armillaria root disease is present, use species observed to have resistance to the fungus in the previous stand. Maintain vigorous growth of young developing stands by thinning. When choice is available, favor resistant species to leave over highly susceptible species. Plan for a minimum number of stand entries over the life of the stand because the creation of large stumps increases the level of inoculum for infection of remaining trees. In heavily infected mature stands where harvest is not planned but increased cover is desired, resistant species sometimes may be interplanted in openings created by the root disease.

References

Goheen, E.M. and E.A. Willhite. 2006. Field guide to common diseases and insect pests of Oregon and Washington conifers. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Portland, OR. R6-NR-FID-PR-01-06. 335 pp. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/80321#/summary

Filip, G.M., J. Brio, K.L. Chadwick, D.J. Goheen, E.M. Goheen, J.S. Hadfield, A. Kanaskie, H.S.J. Kearns, H.M. Maffei, K.M. Mallams, D.W. Omdal, A.L. Saavedra, and C.L. Schmitt. 2014. Field guide for hazard-tree identification and mitigation on developed sites in Oregon and Washington forests. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Portland, OR. R6-NR-TP-021-2013. 120 pp.

Hadfield, J.S., D.J. Goheen, G.M. Filip, C.L. Schmitt, and R.D. Harvey. 1986. Root diseases in Oregon and Washington conifers. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, Portland, OR. R6-FPM-250-86. 27 pp.

Shaw, C.G. III, and G.A. Kile. 1991. Armillaria root disease. USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C., Agriculture Handbook 691. 233 pp.

Williams, R.E., C.G. Shaw III, P.M. Wargo, and W.H. Sites. 1986. Armillaria root disease. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet 78 (revised). USDA Forest Service, Washington D.C. 8 pp.

Website links

Western Forest Insects and Diseases: Publications and Links

Forest Insect and Disease Leaflets - Armillaria Root Disease